Hi people!

A new Cheese Talks article just went live!

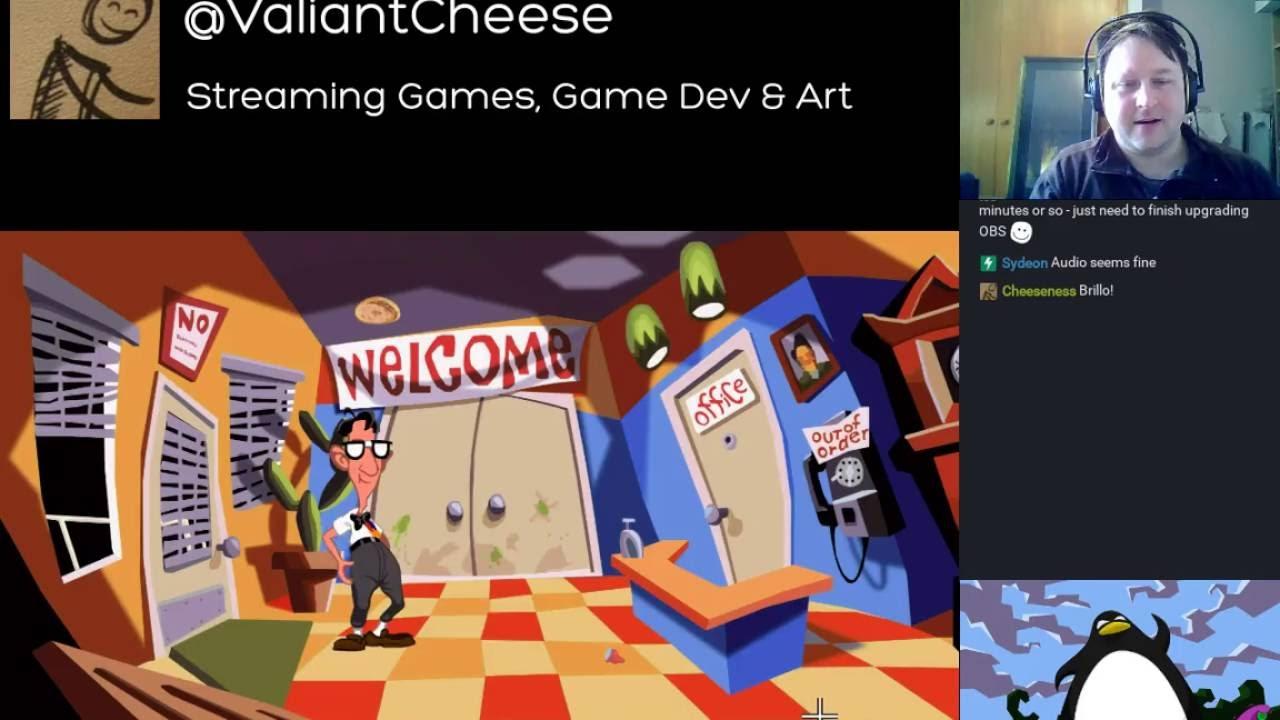

This time, I'm looking back at what I learned from porting Day of the Tentacle Remastered to Linux (see our previous GamingOnLinux coverage here).

In addition to my own thoughts, the article includes insights from a number of other Linux game porters including Leszek Godlewski (Painkiller Hell & Damnation, Deadfall Adventures), Ryan "icculus" Gordon (StarBreak, Left 4 Dead 2, Unreal Tournament 2004, Another World, Cogs, Goat Simulator), David Gow (Keen Dreams, Multiwinia), Ethan Lee (Salt & Sanctuary, Hiden in Plain Sight, HackNet, Waveform, Dust: An Elysian Tail) and Aaron Melcher (Outland, La-Mulana, Hyper Light Drifter, Darkest Dungeon). Betweem them, they offer a great range of attitudes and approaches that support and provide counterpoint to my own experiences.

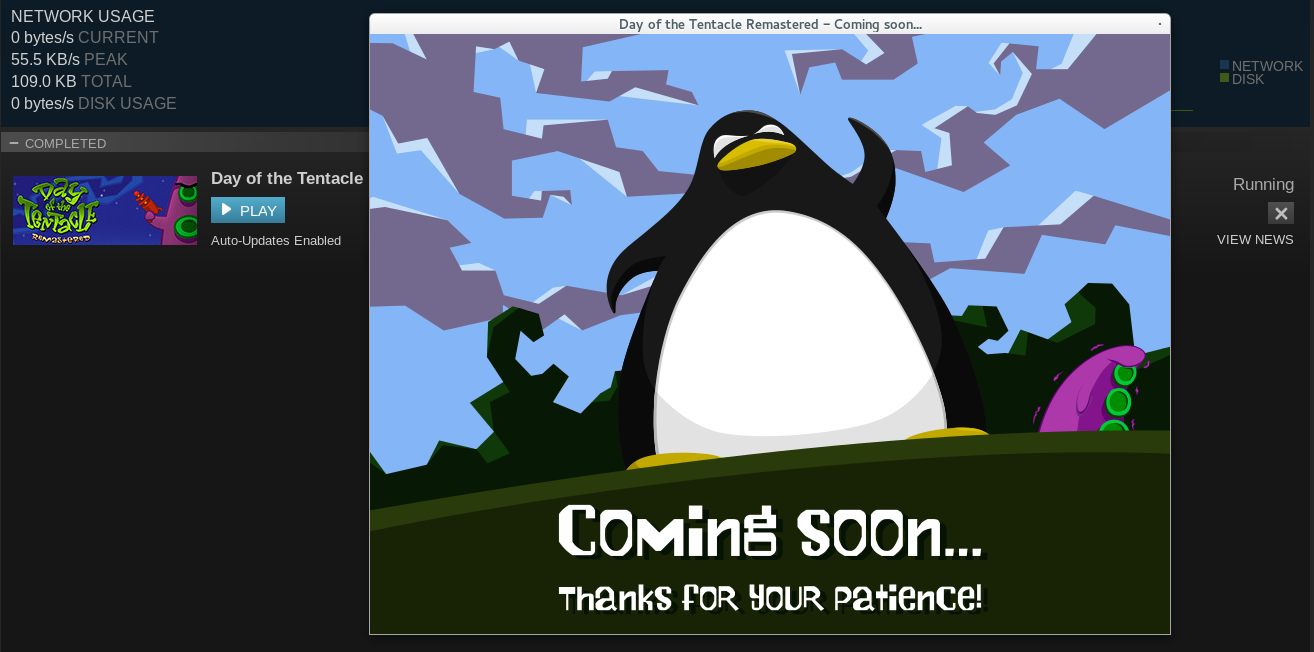

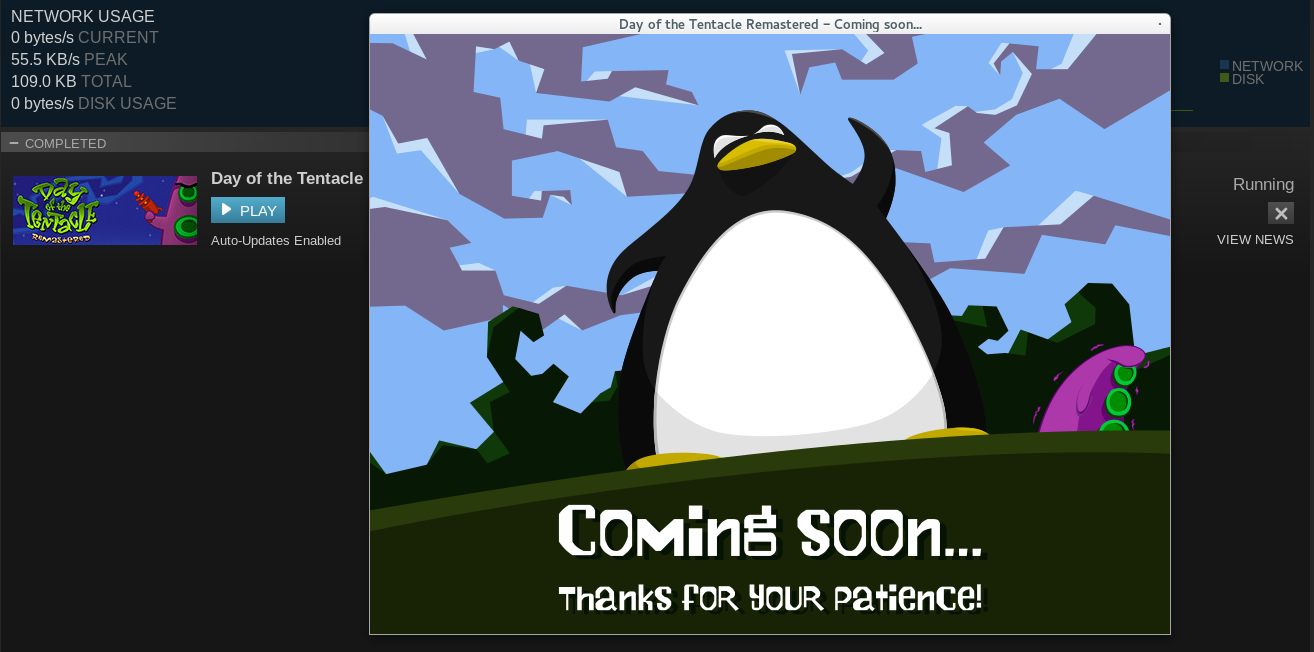

The whole article weighs in at a little over 11,000 words and covers what it's like to get started on a port, and what kind of ups, downs and betweens are likely to be found along the way. As a companion to the article, I've also been able to release the source code for the "coming soon" app that appeared for Linux users on Steam as the game got closer to release.

To whet your apetite and/or give a summary for those who aren't interested reading in the whole thing, here are some snippets.

This article and the Day of the Tentacle Remastered Linux port could not have been possible without the interest and support of Double Fine and the lovely people who work there. Being asked to work on the port was unexpected and I am humbled to have been invited to work on a game I love.

This has been a super huge journey for me, and I'm glad to be able to share my experiences with anybody who's interested.

Enjoy!

Update: I've also published a video with reflections on the game and my experiences of porting it.

A new Cheese Talks article just went live!

This time, I'm looking back at what I learned from porting Day of the Tentacle Remastered to Linux (see our previous GamingOnLinux coverage here).

In addition to my own thoughts, the article includes insights from a number of other Linux game porters including Leszek Godlewski (Painkiller Hell & Damnation, Deadfall Adventures), Ryan "icculus" Gordon (StarBreak, Left 4 Dead 2, Unreal Tournament 2004, Another World, Cogs, Goat Simulator), David Gow (Keen Dreams, Multiwinia), Ethan Lee (Salt & Sanctuary, Hiden in Plain Sight, HackNet, Waveform, Dust: An Elysian Tail) and Aaron Melcher (Outland, La-Mulana, Hyper Light Drifter, Darkest Dungeon). Betweem them, they offer a great range of attitudes and approaches that support and provide counterpoint to my own experiences.

The whole article weighs in at a little over 11,000 words and covers what it's like to get started on a port, and what kind of ups, downs and betweens are likely to be found along the way. As a companion to the article, I've also been able to release the source code for the "coming soon" app that appeared for Linux users on Steam as the game got closer to release.

To whet your apetite and/or give a summary for those who aren't interested reading in the whole thing, here are some snippets.

QuoteMy personal connection to this game has expanded from being that of a player and an appreciator of its accomplishments to include that of a developer and in some respects a historian. I've had the opportunity not only to peek behind the curtain and experience a game I like from a new angle, but I've also been able to look back in time at a fascinating cross-section of LucasArts history. I've seen SCUMM code from the 80s written for Maniac Mansion (in one file, there's a lovely code comment saying there's a front row seat in hell for me if I edit it - I like to pretend that that's Ron Gilbert's "grumpy" persona yelling at me from across the decades), I've seen early 90s work from Day of the Tentacle's development, I've seen the "Remonkeyed" engine code written for the Monkey Island special editions, and I've seen Double Fine's work on adapting that for DotT's remastered edition.

QuoteFrom the outset, I was keenly aware that the codebase I'd be working in was of a scale beyond anything I had contributed to before. I'd been given the opportunity to review the codebase before signing a contract, but that really wasn't enough of a window to get the familiarity that I'd need to deliver a finished port - I'd need to be able to learn as I went without slowing myself down too much.

I set myself up a rough plan that would allow me to focus on achievable things while also exposing myself to more of the codebase as I went, which looked something like this:

* Set up my build environment ahead of time

* Work out-of-tree so that exploration and experimentation doesn't get committed

* Get the codebase to compile (stub out anything that looks like it needs rewriting)

* Sift back through looking for platform specific #if directives that might've been missed

* Look through all build scripts for any platform specific stuff that might've been missed

* Prepare an initial port commit and start working in-tree

* Rewrite any stubbed code

* Focus on fixing crashes/behavioural differences

By treating compilation as my initial goal, I'd be able to make forward progress with zero knowledge of the codebase - compiler errors would tell me where to look, and I'd learn bits and pieces about the project's structure as I went through doing superficial stuff like correcting case issues and making Linux specific copies of other platforms' #if directives.

QuoteSomething that was both expected and a surprise to realise was that my experiences of porting didn't really fall into the realm of what I would normally refer to as programming. In fact, reflecting on my experiences, I feel that it's probably fair to consider that it's a porter's goal to write as little code as possible.

All of the creative/design decisions around code structure, systems behaviour and dependencies are typically locked in place, and deviating from them means a port that's less likely to be maintained once it's completed.

Quote"The other really important thing to know when planning is if you're going to be working on the main branch of the game, or in a separate branch which will likely never be merged. You need to decide how much freedom you have to rewrite or refactor existing code, versus carefully changing only what is required. When in doubt, don't change things you don't have to, and document your changes well." - David Gow

QuoteThis may be a point of contention, as I do know some porters who don't agree with this outlook, but it seems important to me to make sure that I have lines of contact to developers who have previously worked on the project.

If there's a piece of code that needs to be understood before forward progress can be made, and that's either going to take two days to work through alone or twenty minutes' worth of conversation time, then it's pretty clear which approach is in the best interests of the project.

QuoteShortly after getting the Day of the Tentacle running (an early milestone), I had encountered an issue where audio cues were firing incorrectly. Advice from other developers who'd worked on the game was that it was most likely an interrupt loop that controlled the audio system being too far outside of its target 300ms interval, but nothing I tried on that front seemed to help. In an effort to track down the issue, I'd upgraded GCC to gain access to newer compiler flags that I hoped would help me narrow down my problem. In one late night flurry of bugfixes, I'd announced the problem solved by some unrelated commit and moved on.

When the time came to build the project inside the Steam Runtime, which just so happens to ship with GCC 4.8.1, the problem reared its unpleasant head again. After several days of slowly stepping through the game and scrutinising its behaviour, I discovered that somewhere between 4.8.5 and 4.9.2 (I couldn't spot anything useful in the GCC changelogs, and it didn't seem in the project's best interests to spend time digging out the relevant commit), the behaviour of the following C++ syntax, which is undefined in the language spec, had changed.

ptr += some_fuction(&ptr);

The ambiguity arises when this statement can be interpreted as either ptr = ptr + some_function(&ptr) or ptr = some_function(&ptr) + ptr. In the case we care about, the function modifies the value of ptr, and was used to calculate the length of data (say, an int representing how long an audio cue should last) in packed in memory. Instead of getting the correct memory address to read our value from, we end up reading partway through some other value and things spin wildly out of control from there. GCC's -Wsequence-point compiler flag is meant to help identify these kinds of problems, but it seems that the involvement of a function that manipulates the value of ptr confuses things a little.

QuoteOne friend and porter who would prefer to remain anonymous has passed on to me an aphorism that I found amusing: the more time spent on a bug, the smaller the fix. It's meant to be taken as a Murphy's Law type reassurance that tripping up on things that seem small in hindsight is normal, but it reflects some interesting characteristics of problem solving.

Small issues such as the one mentioned above are more easily overlooked, and the longer they wear on, the more frustrating they can become. With each hour, day, week or month that an elusive problem consumes, the number of more-obvious causes it could be hiding under dwindle. We learn about common problems like off-by-one errors and learn to look out for them, but until we've gotten that perspective, it's awfully difficult to spot them for what they are. Some things are just easier to see with experience, I think.

QuoteWhen it came time to move into testing, we encountered a fairly common and awkward situation. To allow access to testers who had normal subscriptions to the game on Steam, we would also be exposing Linux users to partial Steam configuration, which would cause the game to show up in their library and be listed as downloadable. Steam would "download" an empty folder and the first real indication that the player would get of something being wrong would be a misleading "missing executable" error. In other projects I've been involved with, this has generated support requests and grumbles from people assuming that developers don't know what they're doing.

Following the example set by some other porters (Ryan and Ethan in particular have been known to do this), I spent half an hour putting together a quick application that could be placed in the default non-beta branch and let Linux users know that the game was still coming soon.

QuoteRecognising that emotional and psychological state impact heavily on productivity, and making appropriate decisions around when to schedule breaks or recreational activities can help make sure that longer projects don't become overwhelming. In general, being aware of one's personal limits and reactions is important (see my game jam survival guide for some more thoughts on that) for being able to navigate and cope effectively with pressures and constraints.

Typically, I like to keep a rough window of time defined by best-case-scenario estimates and conservative not-so-good guesses for remaining work. When a relevant date (whether it's an external milestone or an internal personal goal) encroaches upon that window, I start adjusting my own expectations and make sure to communicate that upstream to whatever relevant contacts may need to know. Avoiding unpleasant surprises and being able to get the ball rolling on extensions or recalculated timeframes early can help make those (often unavoidable) situations easier to deal with and feel comfortable with.

To help keep track of progress and assist with triaging, I keep a log of thoughts, approaches and solutions for completed work as well as a list of known needed work. Typically this is more verbose and rambling than is appropriate for commit messages, but a bug tracker can be a good fit. Most of the time, I make do with a plain text file.

Having that kind of information available has been super helpful in keeping momentum and feel more comfortable stopping for sleep when in the middle of solving a problem.

Quote"Don't give up, always finish, ask for help, and don't let the work consume you. There can always be patches later. Learn what you can, check your assumptions, do better next time and don't beat yourself up too much. Sleep a little sometimes." - Ryan C. Gordon

QuoteAnybody who has worked on a big project will know that there's an adjustment period following the intensity of release. When working in teams, camaraderie and shared experience make this easier to work through. The ability to interact with communities and critics, to speak to and for one's work can be cathartic as well.

Many porters (particularly solo porters) don't have the same avenues for support. Porters generally are not authorised to speak on behalf of their employers, and without much creative input, the sense of personal investment can be diminished (to me, Day of the Tentacle is not, and never will be "my game"). The opportunities for working through "post release blues" are often very different for contractors.

For some projects that I've worked on, doing post-release support has been a nice way to wind down after a release, and doing volunteer outreach and tech support for Linux users that I've come across has been nice in that way. I can fully appreciate though, that this kind of direct community contact is not something that all porters are likely to find enjoyable or have permission to engage in.

QuoteFrom the work done by Matt, Oliver and the rest of the DotT Remastered team; through to Craig Derrick's and the Monkey Island Special Editions' teams' efforts; Tim, Dave and the original DotT team's work; and all the way back to Ron, Chip and Aric's work on the original SCUMM engine, the codebase I inherited for my port was well designed and (so much as these things can be) a delight to work with. I am very thankful to have been able to "work with" such talented people on well-made software.

This article and the Day of the Tentacle Remastered Linux port could not have been possible without the interest and support of Double Fine and the lovely people who work there. Being asked to work on the port was unexpected and I am humbled to have been invited to work on a game I love.

This has been a super huge journey for me, and I'm glad to be able to share my experiences with anybody who's interested.

Enjoy!

Update: I've also published a video with reflections on the game and my experiences of porting it.

YouTube videos require cookies, you must accept their cookies to view. View cookie preferences.

Direct Link

Direct Link

Some you may have missed, popular articles from the last month:

Really cool is that one to read, mentioned in the original article (I seem to have missed it):

https://icculus.org/~icculus/dotplan/SeriousSam-CHANGELOG.txt

Daily log updates of the SeriousSam port of Ryan (icculus) Gordon, but writing not what has been done but what he's planning to do. Expect a lot of disappointment, and less "yyeeey" moments ;-).

Another interesting part is:

> Porting Is Not Software Development

porting is like fixing a huge mess of a bug with a code structure you don't like, but you have to focus on rewriting as little as possible. Which is the usual bugfix procedure (if fixing the bug of somebody else). Changing less means less possibilities to break. Had to experience that the hard way, "that's done bad, this could be done better" ending up in fixing what i "fixed" or "beautified".

I didn't port games yet, but I did port some more-or-less complex applications from Windows to Linux (codebase between 50.000 loc and 300.000 loc) knowing that very well, especially if you do know windows and are crazy enough starting to touch the windows implementation because you think you can do better with almost no effort than the windows guys who were paid for it. Never do that. Ever. Seriously. Get some fuel and a lighter, will be less pain and a faster end.

But really cool article to read, great that this one was shared. Thanks!

Last edited by STiAT on 24 July 2016 at 1:49 am UTC

https://icculus.org/~icculus/dotplan/SeriousSam-CHANGELOG.txt

Daily log updates of the SeriousSam port of Ryan (icculus) Gordon, but writing not what has been done but what he's planning to do. Expect a lot of disappointment, and less "yyeeey" moments ;-).

Another interesting part is:

> Porting Is Not Software Development

porting is like fixing a huge mess of a bug with a code structure you don't like, but you have to focus on rewriting as little as possible. Which is the usual bugfix procedure (if fixing the bug of somebody else). Changing less means less possibilities to break. Had to experience that the hard way, "that's done bad, this could be done better" ending up in fixing what i "fixed" or "beautified".

I didn't port games yet, but I did port some more-or-less complex applications from Windows to Linux (codebase between 50.000 loc and 300.000 loc) knowing that very well, especially if you do know windows and are crazy enough starting to touch the windows implementation because you think you can do better with almost no effort than the windows guys who were paid for it. Never do that. Ever. Seriously. Get some fuel and a lighter, will be less pain and a faster end.

But really cool article to read, great that this one was shared. Thanks!

Last edited by STiAT on 24 July 2016 at 1:49 am UTC

2 Likes, Who?

Quoting: STiATReally cool is that one to read, mentioned in the original article (I seem to have missed it):

https://icculus.org/~icculus/dotplan/SeriousSam-CHANGELOG.txt

Daily log updates of the SeriousSam port of Ryan (icculus) Gordon, but writing not what has been done but what he's planning to do. Expect a lot of disappointment, and less "yyeeey" moments ;-).

That is a super cool piece of historic treasure, and I'm really happy that Ryan was able to share it.

For anybody who hasn't read it, it's probably important to read this introduction to get some extra context for that changelog.

I'd have loved to have shared mine, but my commit history was pretty boring and my daily log is mostly shorthand gibberish that wouldn't mean anything to anybody :D

Quoting: STiATporting is like fixing a huge mess of a bug with a code structure you don't like, but you have to focus on rewriting as little as possible. Which is the usual bugfix procedure (if fixing the bug of somebody else). Changing less means less possibilities to break. Had to experience that the hard way, "that's done bad, this could be done better" ending up in fixing what i "fixed" or "beautified".

This is very true, although I find that it's not necessarily that things were "bad", but often just that they weren't done in the way I like to do things. Since you don't get to see or be involved with the decision making processes, it's easy to assume that everybody was making bad decisions, when at the time, everybody was working hard and doing the best with what they had.

You're totally right about fixing up and making things pretty being a trap. If you start down that road, you'll be shaving yaks before you know it and will probably have broken other platforms along the way >_<

1 Likes, Who?

ptr += some_fuction(&ptr);

Heheh... Yeah, that's the thing about C and C++. They give smart people the ability to make exceedingly dumb decisions.

It's powerful how much low level access in a high level language you have to memory locations and variables, etc. But with great power comes great responsibility. And so many clever programmers are prone to making "cute" little syntactical shortcuts like this, even though they don't have to. And it just makes it harder to maintain... Even for Mr Clever himself, if/when he comes back a year later to regression test or change functionality / refactor.

I've learned over the years when I hit a spot of code where I'm starting to write "clever" code... After many many times of coming back later for some kind of change or upgrade and hitting a brick wall. Just literally staring at my own code until I spent more time than I wanted unraveling a tightly wrapped train of reasoning that was only clear in my head for a brief moment in time after a day or two of working with it originally..

I've learned, man. When I hit those spots now writing new code, I stop - oh no, I know what this is. Let's step back and take our time, lots of REM statements, long descriptive variable names. As a matter of fact, let's just think about what we name the variables as long as the code we're going to use them in...

That's one nice thing about open source code, many times it's been cleaned up internally just because you know it will be judged by other programmers. It's funny reading all the apologies from coders who decide to release their proprietary project on Github or something similar. They begin to realize people will now be looking at all the "shotgun code" and band-aides they left under the hood.

Heheh... Yeah, that's the thing about C and C++. They give smart people the ability to make exceedingly dumb decisions.

It's powerful how much low level access in a high level language you have to memory locations and variables, etc. But with great power comes great responsibility. And so many clever programmers are prone to making "cute" little syntactical shortcuts like this, even though they don't have to. And it just makes it harder to maintain... Even for Mr Clever himself, if/when he comes back a year later to regression test or change functionality / refactor.

I've learned over the years when I hit a spot of code where I'm starting to write "clever" code... After many many times of coming back later for some kind of change or upgrade and hitting a brick wall. Just literally staring at my own code until I spent more time than I wanted unraveling a tightly wrapped train of reasoning that was only clear in my head for a brief moment in time after a day or two of working with it originally..

I've learned, man. When I hit those spots now writing new code, I stop - oh no, I know what this is. Let's step back and take our time, lots of REM statements, long descriptive variable names. As a matter of fact, let's just think about what we name the variables as long as the code we're going to use them in...

That's one nice thing about open source code, many times it's been cleaned up internally just because you know it will be judged by other programmers. It's funny reading all the apologies from coders who decide to release their proprietary project on Github or something similar. They begin to realize people will now be looking at all the "shotgun code" and band-aides they left under the hood.

2 Likes, Who?

Quoting: CheesenessThis is very true, although I find that it's not necessarily that things were "bad", but often just that they weren't done in the way I like to do things.

Ye well, that would be bad in my definition ;-). Everything not done the way I like it must be bad. I've bit of a Torvalds-Attitude there, which can be a huge issue.

0 Likes

Quoting: STiATQuoting: CheesenessThis is very true, although I find that it's not necessarily that things were "bad", but often just that they weren't done in the way I like to do things.

Ye well, that would be bad in my definition ;-). Everything not done the way I like it must be bad. I've bit of a Torvalds-Attitude there, which can be a huge issue.

Nah, Linus occasionally getting inappropriately (and sometimes, just flat weirdly) upset about minor intra-Linux things is not equivalent to the quote. Every programmer who has to work on someone else's code can face this. Sometimes people think differently than you do. And if you have to make the code work now, you naturally would like it to be modeled around your style of logic, just so you can move forward easier.

There's usually 1,001 ways to go about any given task in coding, so this happens a lot.

But then there's the other side of that coin, sometimes you get code from someone else that is beautiful to look at, you want to copy its paradigms, learn from it. Improve your own style of coding by studying it.

1 Likes, Who?

Nice, thank you.

0 Likes

Very nice and detailed article but it didnt answer my basic noob questions , just some questions from a noob respective

Well I havent done any programming since like 15-20 years , so I wonder How hard is to get to the industry ? I mean what do you have to know? what I have to read? What programming languages you have to know? Are there any specific tools that you need for the porting? Do I need to know assembly ? Physics? Math? Gaming Engines? What compiler to use? etc etc.... PANIC MODE!!!

For me is like an endless road of knowledge , tools and information that I would just simply give up.

I would love to hear how you started with all these.

Well I havent done any programming since like 15-20 years , so I wonder How hard is to get to the industry ? I mean what do you have to know? what I have to read? What programming languages you have to know? Are there any specific tools that you need for the porting? Do I need to know assembly ? Physics? Math? Gaming Engines? What compiler to use? etc etc.... PANIC MODE!!!

For me is like an endless road of knowledge , tools and information that I would just simply give up.

I would love to hear how you started with all these.

0 Likes

Quoting: HalifaxHeheh... Yeah, that's the thing about C and C++. They give smart people the ability to make exceedingly dumb decisions.Ha ha, I know right. "Enough rope to hang yourself."

At the end of the day, you have to accept that people are typically working towards making sure that stuff works rather than stuff that specifically adheres to spec. Not a lot of programmers have complete awareness of what results in undefined behaviour, and certain (*cough cough*) compilers don't bother to highlight that too. It's easy to end up with a "this is what works for me" picture of things if out-of-spec code just happens to behave the same on every compiler and platform you usually work with.

I overlooked that line myself so many times ^_^

Quoting: HalifaxI've learned, man. When I hit those spots now writing new code, I stop - oh no, I know what this is. Let's step back and take our time, lots of REM statements, long descriptive variable names. As a matter of fact, let's just think about what we name the variables as long as the code we're going to use them in...That's a good way to be. It's crazy to me that people seem to forget that 3rd generation languages exist to make things easier to read and work with. There's not much value at all in the fancy code that some people use to make themselves feel cool - the optimiser is only going to rewrite it anyway.

Quoting: HalifaxThat's one nice thing about open source code, many times it's been cleaned up internally just because you know it will be judged by other programmers. It's funny reading all the apologies from coders who decide to release their proprietary project on Github or something similar. They begin to realize people will now be looking at all the "shotgun code" and band-aides they left under the hood.I feel like that's normal though - you sort of need more eyes and more time to mature (which in my experience most proprietary projects don't get because people only get put where the money is - in new features or new projects). Everybody's code is awful until it's been worked over a few times.

Quoting: HalifaxThere's usually 1,001 ways to go about any given task in coding, so this happens a lot.Well said!

But then there's the other side of that coin, sometimes you get code from someone else that is beautiful to look at, you want to copy its paradigms, learn from it. Improve your own style of coding by studying it.

Quoting: wolfyrionVery nice and detailed article but it didnt answer my basic noob questions , just some questions from a noob respectiveAlrighty, let's take a look at these!

Quoting: wolfyrionWell I havent done any programming since like 15-20 years , so I wonder How hard is to get to the industry ?So far as porting goes, I've never chased a port, so I have no idea.

I've been an active and prominent member of the Double Fine community and have been running community events for years. I've also helped out with a few Linux issues here and there, and I think that that close proximity/high visibility as a cool Linux user who does stuff played a big role in me being offered the job.

In addition to the community work and general Linux help I'd given Double Fine contributing to me landing the port, I think some of the other developers I'd worked with over the years had put in a good word for me here and there (and vice versa). It's not uncommon for me to hear from one developer I've helped that they talked to someone who had nice things to say about me at E3 or GDC or PAX or where ever.

Maybe that's what it takes to break into the market - build meaningful relationships with people over half a decade and consistently demonstrate enthusiasm and ability. If that's the case, then that's not a good path - that's a lot of unpaid work right there.

Quoting: wolfyrionI mean what do you have to know? what I have to read? What programming languages you have to know?I'm not sure - I've never really read anything about porting before and leaned heavily on my own experience as a Linux based game developer and awareness of what porter friends have gone through.

The only language you really need to know is the language that the game you're porting was written in.

Quoting: wolfyrionAre there any specific tools that you need for the porting? Do I need to know assembly ? Physics? Math? Gaming Engines? What compiler to use? etc etc.... PANIC MODE!!!I'd say it depends on the project. I didn't touch do assembly with DotT. I didn't really touch any game code since that's all abstracted out from the platform specific code that I spent most of my time on.

For compilers, GCC and Clang are probably your best bet (but again, depends on the project). I did DotT's Linux builds with GCC, but also built the game with Clang. Building in multiple compilers is never a bad thing and can sometimes reveal stuff you might not have noticed.

If the game's written in a generic engine that you can get source for, definitely chase up that. If not, then you're as on your own as you would be with a game that was developed using a custom engine. You're not making a game, so to me, there doesn't seem to be much value in knowing how to use the engine to create a game - you're only adapting stuff that other people have made.

Physics and maths skills are good to have (I don't have these and wish I did), but I think in general, you're not likely to come across any of that kind of code that is platform specific. More important than those skills is the ability to read, comprehend, research and learn on the fly. It's less about what you know and how quickly you can find stuff if that makes sense? Programming's like that in general though IMO.

This quote from the super insightful David Gow is definitely worth taking onboard, I think:

QuoteDon't worry too much about having to know everything going in — not every port requires a knowledge of everything, and every port will involve learning a whole bunch of new things, be they languages or APIs or version control systems. Also, don't be afraid of asking for help — every porter I've met has been really friendly, and will no doubt be more than happy to answer questions, or give advice.

Quoting: wolfyrionFor me is like an endless road of knowledge , tools and information that I would just simply give up.I feel like there are lots of different valid approaches here, and that because of my background my side-activities, I don't I make for a good example (I honestly don't think any one person can, and that's something I hope is reflected in the various porters' quotes that I've included in the article).

I would love to hear how you started with all these.

I have a mostly comprehensive list of Stuff I've Done over here, but it's probably difficult to put into a chronology. Here's a quick rundown on the stuff that seems relevant.

I first started programming in the 80s. My family got an Amiga 500 when I was 7 or 8, and my Dad and I learned to program together by copying examples out of computer magazines. Mostly I messed around with AmigaBASIC and AMOS at the time.

Later, when I got the laptop mentioned at the beginning of the article, I made a bunch of dumb stuff with QBASIC, VisualBasic and some other junk that I can't remember (maybe some Delphi thing? I have no idea).

I continued doing programming at school, but didn't really learn anything I hadn't already discovered on my own. I picked up Pascal, Python, Java and C/C++ along the way.

In the nearly 2000s, I put together a small team and started working on some Half-Life 1 mods. I didn't do much programming on those and mostly focused on game design and asset creation. It was around this time that I decided that making games was something I wanted to do (note, porting isn't making games).

I switched to Linux a little while after that and started contributing to Neverball in my spare time. The goal was to use my day jobs (I did pizza delivery, retail, helpdesk, sysadmin, app dev and embedded dev) to get stable enough to start my own game dev studio, but that never really happened.

Around 2011, I started being more visibly active in Linux gaming circles, started tracking Humble stats and helped form the initial SteamLUG community that grew out of the long running SPUF Linux thread. I was also prominent in the Desura community and became a Desurium contributor when the client was open sourced. I feel that all this sort of platform advocacy and community engagement stuff has been helpful in having other developers take me seriously.

From this point on, I started making myself available to assist developers who were interested in supporting Linux as a favour. I never really thought much of it at the time and never kept records. Mostly I was just giving reassurance, offering advice on how to package things and helping identify bugs and stuff. I think between then and now, I've helped in that manner with maybe 50 titles?

Around this time, my friend flibitijibibo (Ethan Lee) did his first port, and ended up getting working with Humble to help cope with the increased demand for Linux support that their "must be cross platform" requirement drove. Linux porters seemed to be in high demand (everybody was busy). I was approached to do some Linux ports, but turned them down (some trivia: Bohemia were among these - I'm really happy to know they finally got Arma3 onto Linux!). They weren't titles I was interested in, and I wanted to make my own games, not other people's.

I started making my own games again in earnest in 2012 after recovering from a repetitive strain injury. I ended up in a small team working on a game for the first 7DFPS. From that point forward, I have had at least one game development project on the go at any given point in time.

When Double Fine launched their crowdfunding campaign for what would eventually become Broken Age, I became active within their community, organising backer meetups, community development projects and taking over Game Club when it became too much for DF's Greg Rice to run on his own. I was motivated to do all this stuff by the company's enthusiasm for and commitment to Linux (and because their games were cool). As time wore on, I eventually made friends with a bunch of people who work there and was asked to help do informal pre-release Linux testing on a few projects.

When I heard that a simultaneous release for DotT Remastered wouldn't be possible, I offered to help out in any way that would make it easier for them, and eventually negotiated to help with QA. Toward the end of March, I was offered the port, which coincided with timeframes I had for looking for contract work to boost my savings so that I could keep doing my own game dev. By the end of April we had agreed on contract terms, and I started work on May 1st (not including the time I spent looking over the code before signing the contract).

Hope that helps!

4 Likes, Who?

Quoting: CheesenessMore important than those skills is the ability to read, comprehend, research and learn on the fly. It's less about what you know and how quickly you can find stuff if that makes sense? Programming's like that in general though IMO.This is my experience exactly. I don't think I've ever done a project that didn't require learning something new. Be it a new API or framework or toolkit or a database system or whatever. And that's one part of why I like this job despite the stress and the unpredictability of being self-employed in this field. I guess I get bored easily.

One thing that always gives me mixed feelings is the weird notion people have of this work (software design) being somehow glamorous or requiring some very specific and rare talent or genius, when the only thing that's absolutely required is some creativity and masochistic levels of patience.

1 Likes, Who?

A fantastic read, Cheese. Can't wait to play the game!

0 Likes

Currently working on Winter's Wake, a first person text adventure thing and its engine Icicle. Also making a little bee themed base builder called Hive Time :)

I do more stuff than could ever fit into a bio.

See more from me